Aikido as Meditation

In the Dojo Volume 3 Issue 1

By Josh Paul Sensei, AOSB head instructor

“Victory over oneself is the primary goal of our training. ”

Meditation and aikido, as well as other martial arts, have a long, intertwined history. My first aikido teacher, Joseph Jarman sensei, was a Zen Buddhist priest, and regularly led zazen (seated meditation) and kinhin (walking meditation) sessions after class. Aikido and meditation may be practiced independently or as complements to one another. Or one can pursue aikido as a form of meditation unto itself.

Joseph Jarman sensei

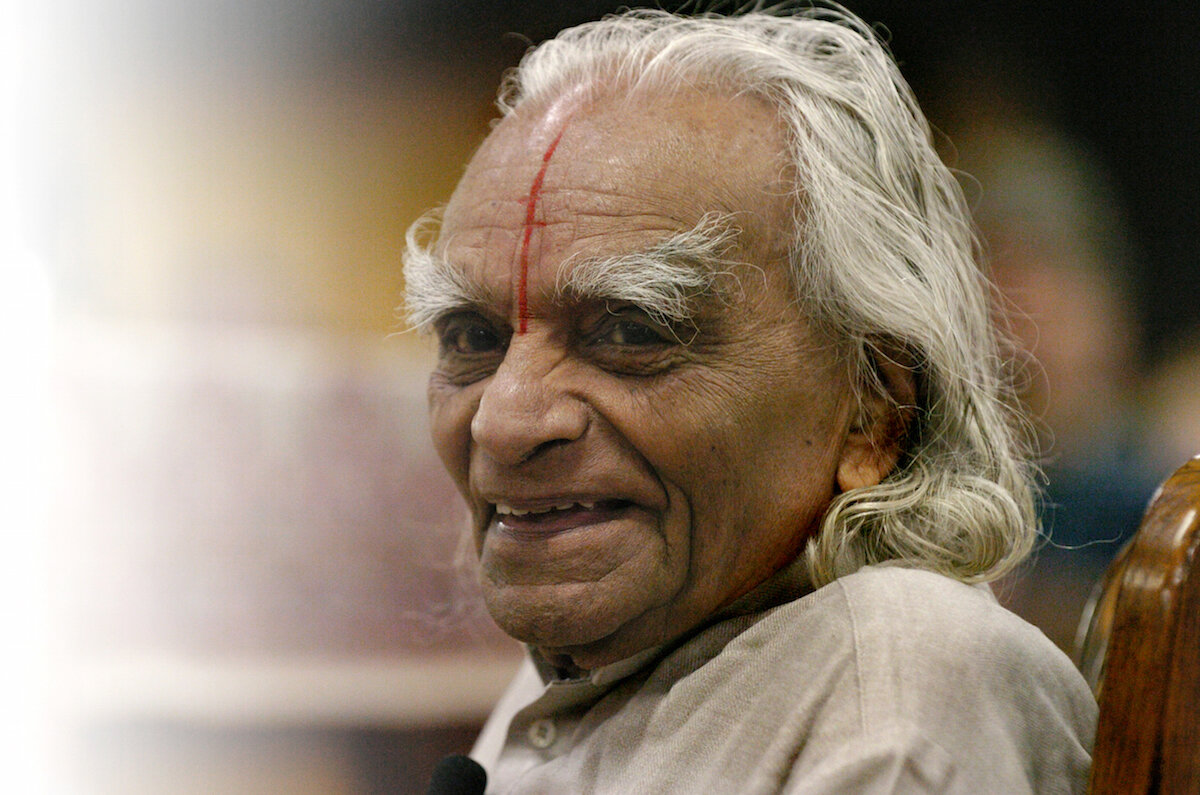

In The Tree of Yoga, BKS Iyengar, one the yoga teachers from India who brought yoga to the West, says that, “focusing on one point is concentration. Focusing on all points at the same time is meditation.” In yoga, he says, our tendency is to practice with partial attention: to focus so intently on one detail that we lose sight of others. For example, while concentrating on straightening our arms, we forget about the actions occurring in our legs. Or we might concentrate so completely on foot position that we lose our posture. However, by keeping all actions in mind, he says, we can achieve meditation.

BKS Iyengar

This is as true for aikido as it is for yoga. The power achievable in aikido technique comes from a unified use of body and mind. However, as with the yogi, partial attention is also a challenge for the aikidoka. When our teacher or partner brings awareness to our hands, we often forget our feet. When our awareness is called to our feet, we might lose our posture. And when we become overly preoccupied with anticipating our partner’s next atemi or technique, we may lose our composure completely. For aikido to work physically and mentally, mind and body must work together as a single unit. We must focus on all points at the same time. Practice should be a meditation.

O’Sensei practicing tai no henko.

Mr. Iyengar also says that “analysis in action” is necessary to achieving a correct pose. Too often, he says, “you do the pose, but you don’t reflect in it.” Think of an aikido exercise like tai no henko. How often do we go through the movements without reflecting on our beginning, middle, and end posture; whether we have tension in our lower back; if the bend in the knees is too much or too little; if our footprint on the mat is even? And how often do we practice the exercise without any reflection on how we feel or our thought process? That is, how often do we practice a core exercise without meditation?

Focusing on all points of one’s body simultaneously, analyzing movements in real time, and adjusting in large and infinitesimally small ways to produce a better technique and stronger, more refined spirit is aikido at its very core.

Much of what we do in the dojo is metaphorical. We create conflict so that we can reflect on how we respond to it. Do we fight or try to run away? Do we experience anger and despair, or blame and guilt? Do we meet aggression with aggression or can we acknowledge and accept the conflict and move into it to create something new? How often do we see beginners whose instinctual response to being grabbed is to grab back?

It is through these processes that we learn more about ourselves and how to better respond to and resolve the conflicts that revolve around us. It is the path to “victory over oneself.”